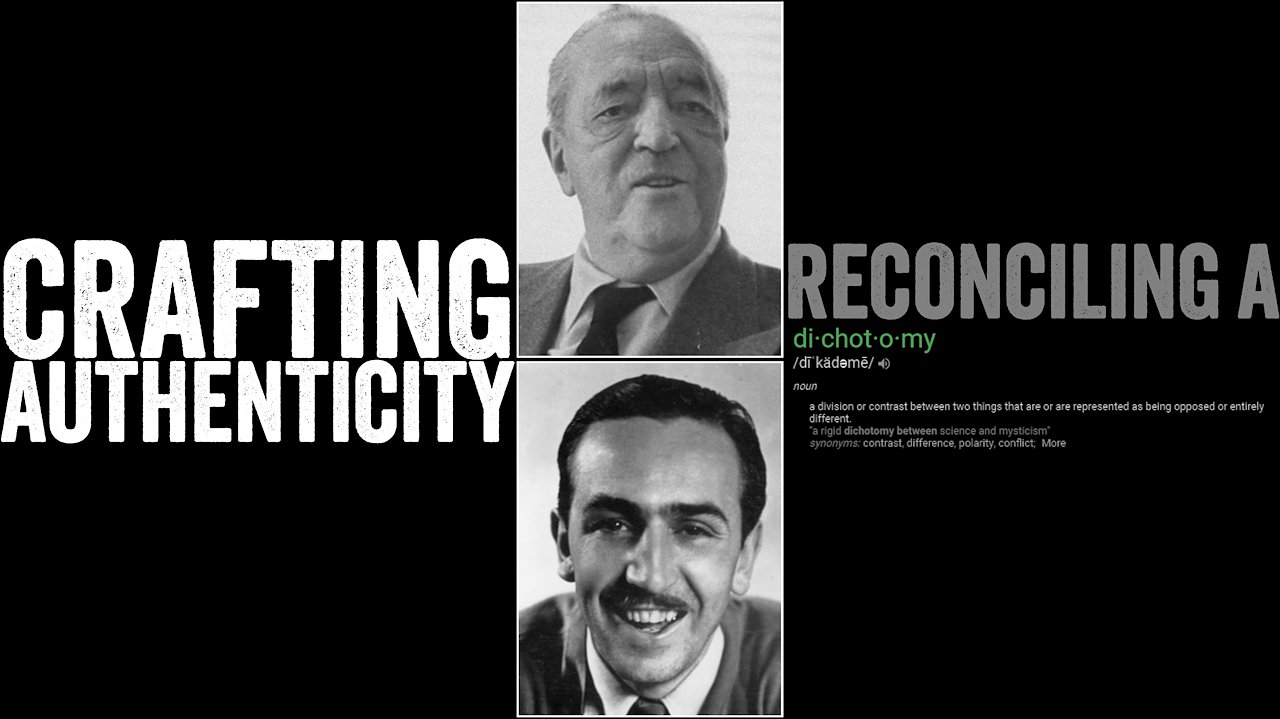

01_I’m here to discuss a dichotomy. Growing up in Southern California, I found myself drawn to architecture as a means to design theme parks. In my pursuit though, I found a new passion in contemporary architecture - but it has always seemed to contradict my inherent love of theme parks, and most specifically, Disneyland.

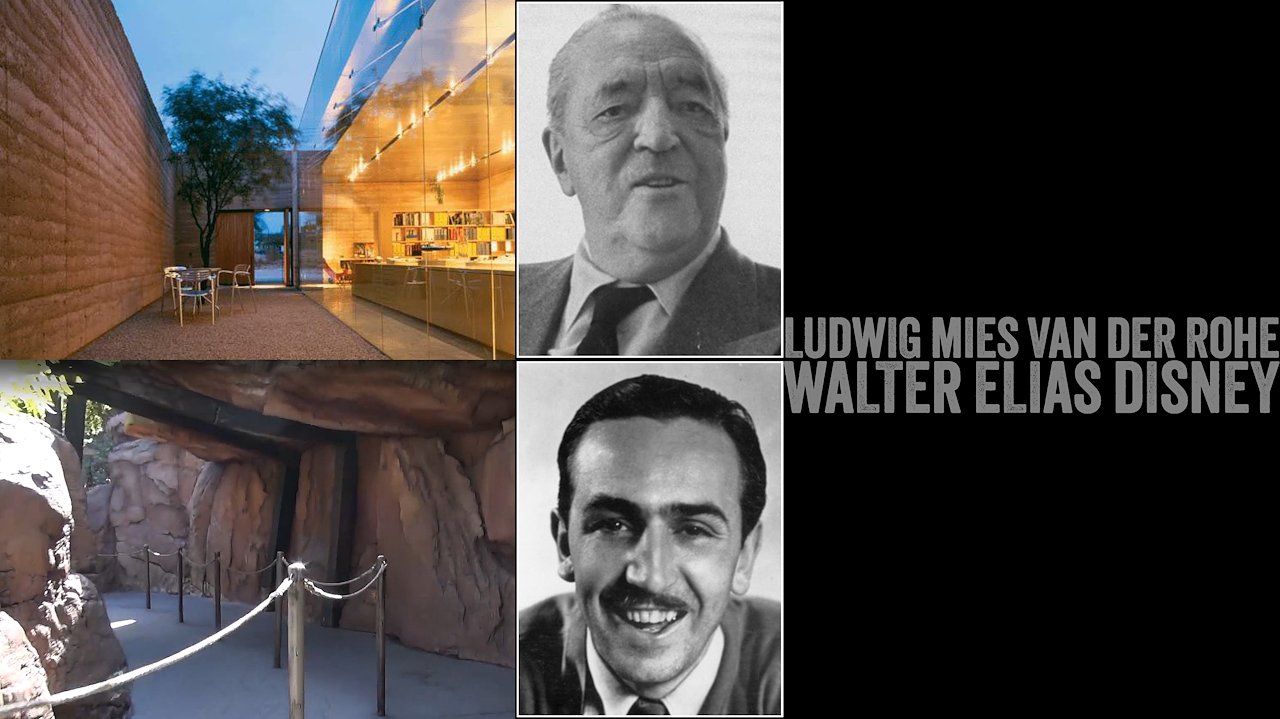

02_So herein lies my desire to reconcile a connection between someone like Mies van der Rohe, a founding father of the modernist architecture movement - and Walt Disney, an innovator of the same time period that transformed the traditional amusement park into a new typology of experiential based design.

03_Now I know what you’re thinking - as I’ve heard it directly: “You mean that corporate mouse that demands every dollar from my wallet while trying to sell me magic?” While the name Disney has been known to become synonymous with corporate profits, I argue that the genesis and underlying foundation of their design standards have always been rooted in crafting authentic experiences, especially through the details of each project.

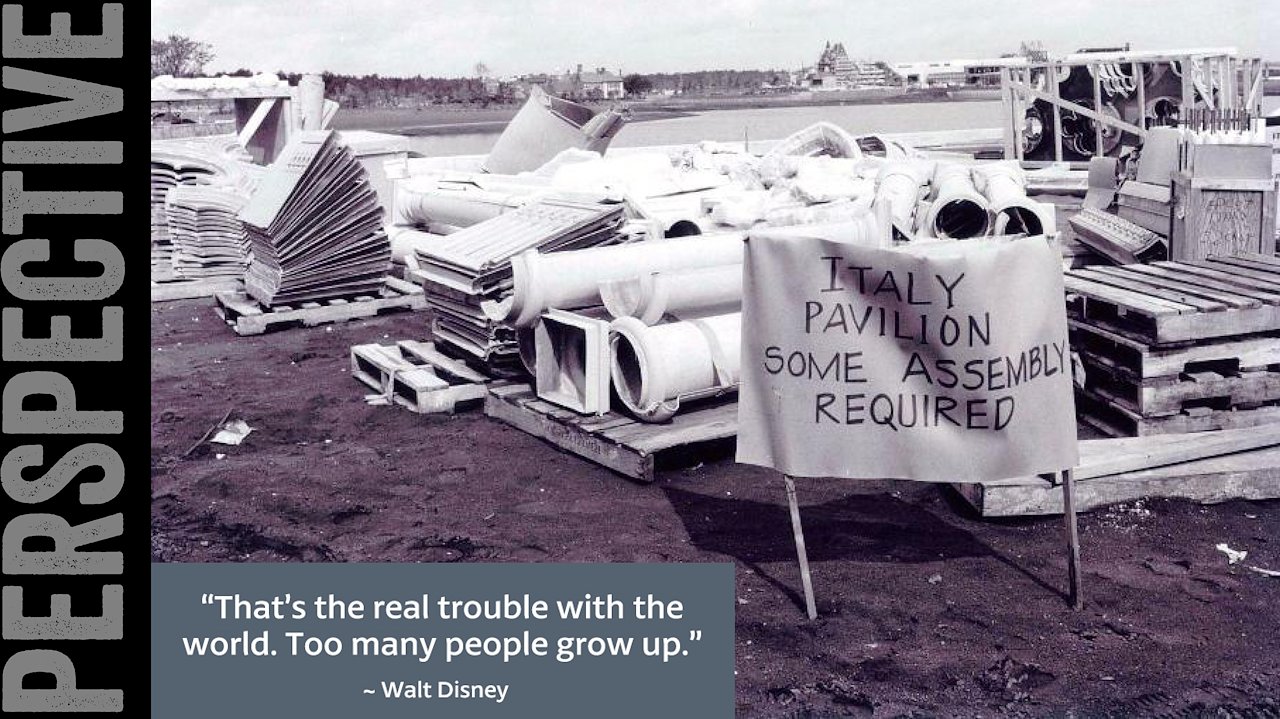

04_Within this argument of authenticity - Disneyland is what it is, a theme park. It never claimed nor still claims to be “the real thing” - but a place that utilizes real-world connections to craft more idealized experiences. I argue that most people tend to take the argument too seriously and thus brush off Disneyland as somehow illegitimate because of its program as a theme park, versus a more “legitimate” custom residence or commercial office building.

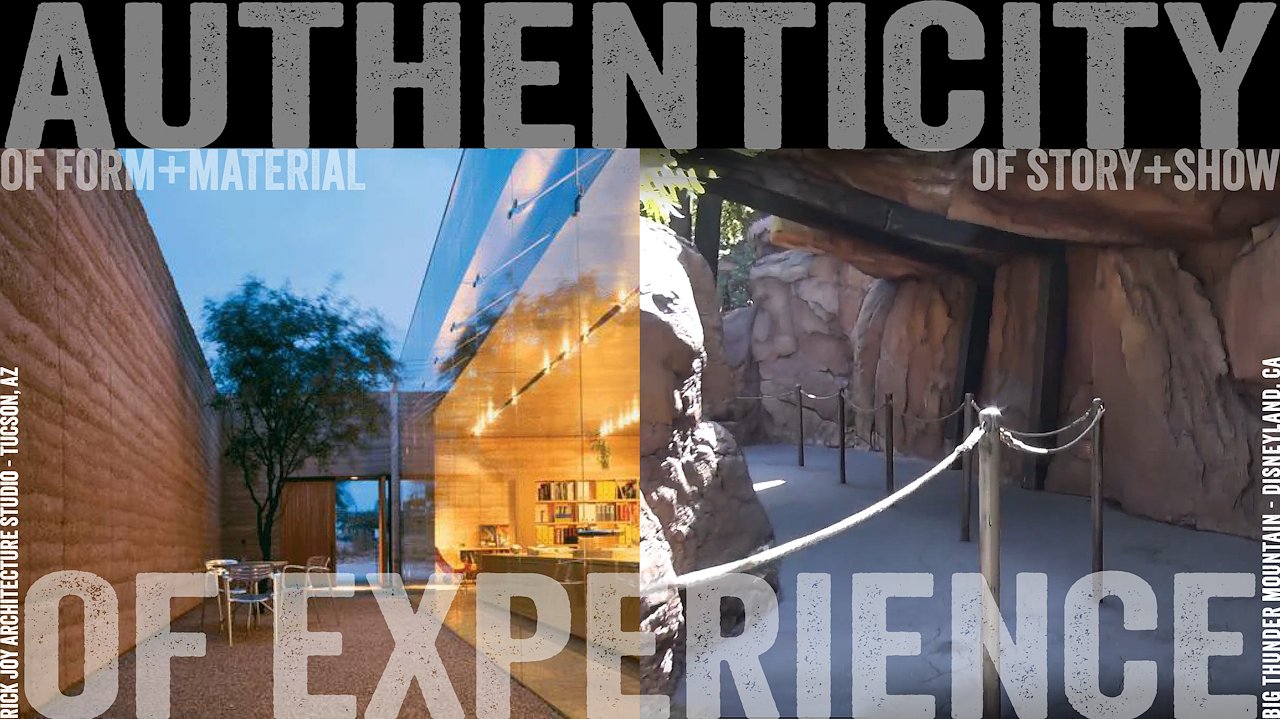

05_This “authenticity of experience” is at the heart of the dichotomy. Is there a difference between a rammed earth wall juxtaposed against tempered glass, or a broken wooden beam precariously holding up a boulder overhead in an old mining town? I say no, as both are crafting an experience. Whereas modern architecture focuses on the art of form and material, Disneyland is a masterclass in the art of the immersive narrative, of show and story.

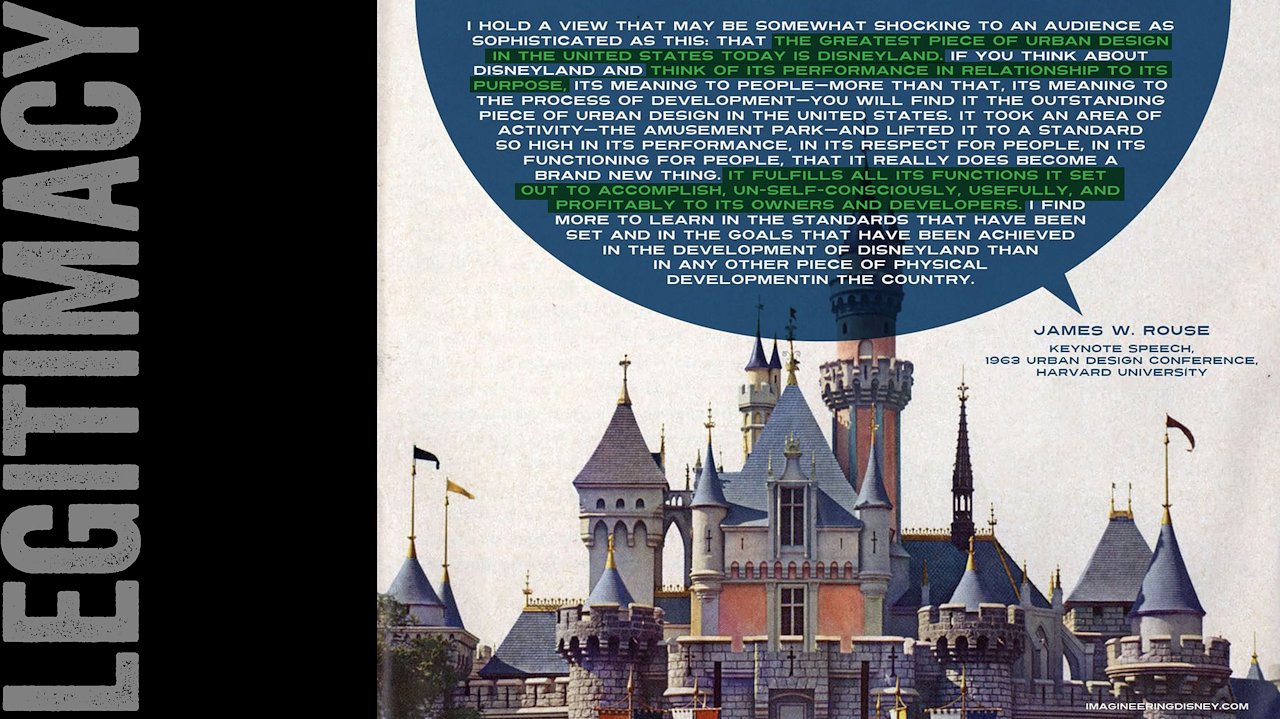

06_At a keynote speech in a 1963 Urban Design Conference at Harvard, it was said that: “the greatest piece of urban design in the United States today is Disneyland…think of its performance in relationship to its purpose…It fulfills all its functions it set out to accomplish, unselfconsciously, usefully, and profitably to its owners and developers.”

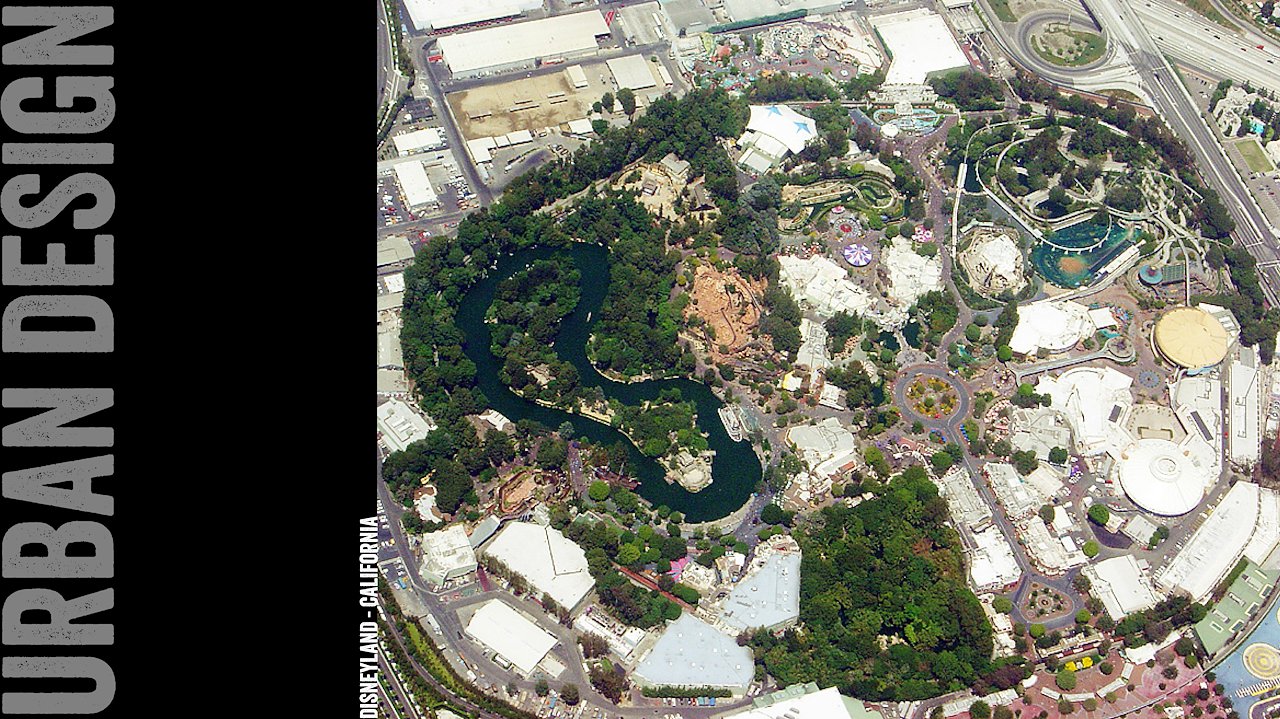

07_Disneyland’s hub concept is key to this user experience, distinct themed neighborhoods that blend seamlessly together. This layout provides a subconscious understanding - you can wander aimlessly around the park or, navigate exactly where they want to go without the need for signage.

With that, let me step back and start to look at the individual elements that we typically associate with “legitimate architecture”:

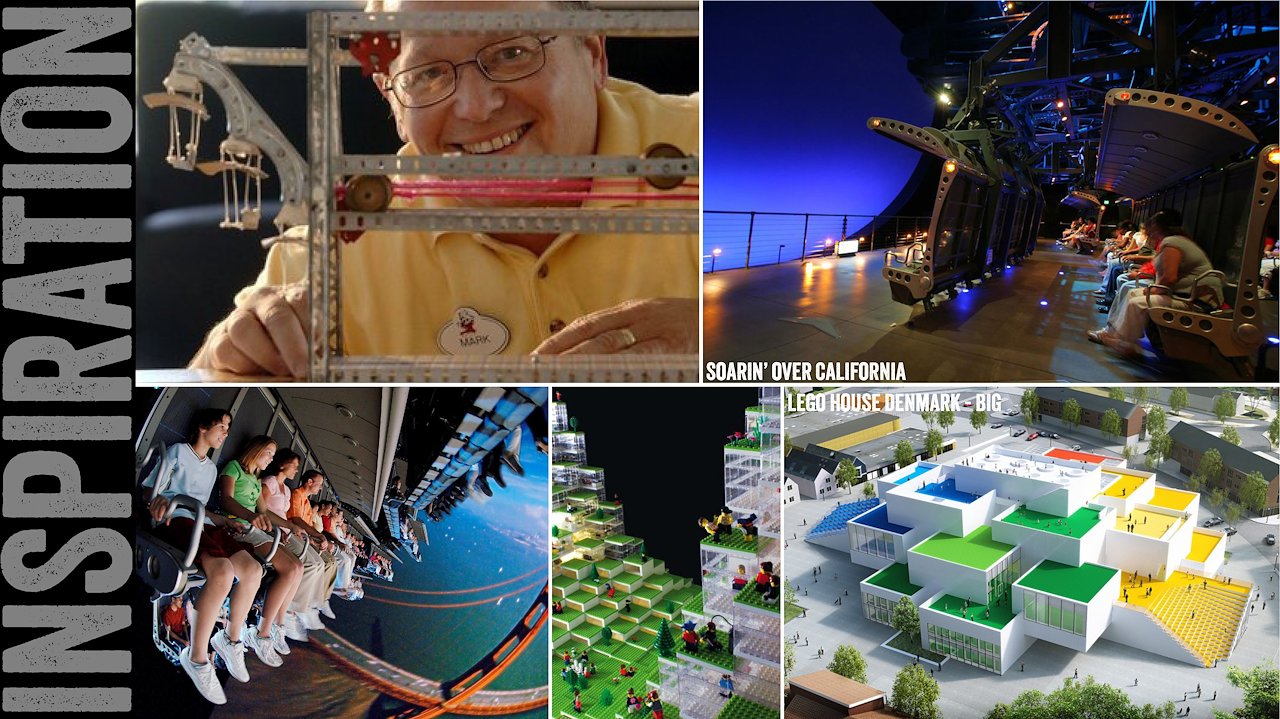

08_Inspiration: One of the most successful modern Disney rides is Soarin’ Over California - which takes guests on a simulated hang-glider ride over various iconic California sites. The mechanical ride system itself, originally thought to be too complicated to build, was finally conceived using a childhood erector set. Like Legos, modern architects and Imagineers are playing with the same toys and tools.

09_Orientation: Orienting a project on a site is a fundamental step in site planning. No different in a Disney theme park. Each of the parks are setup so that their iconic buildings, typically the castle, are facing south - so that they are never in shadow and always create the best photographic opportunity for guests.

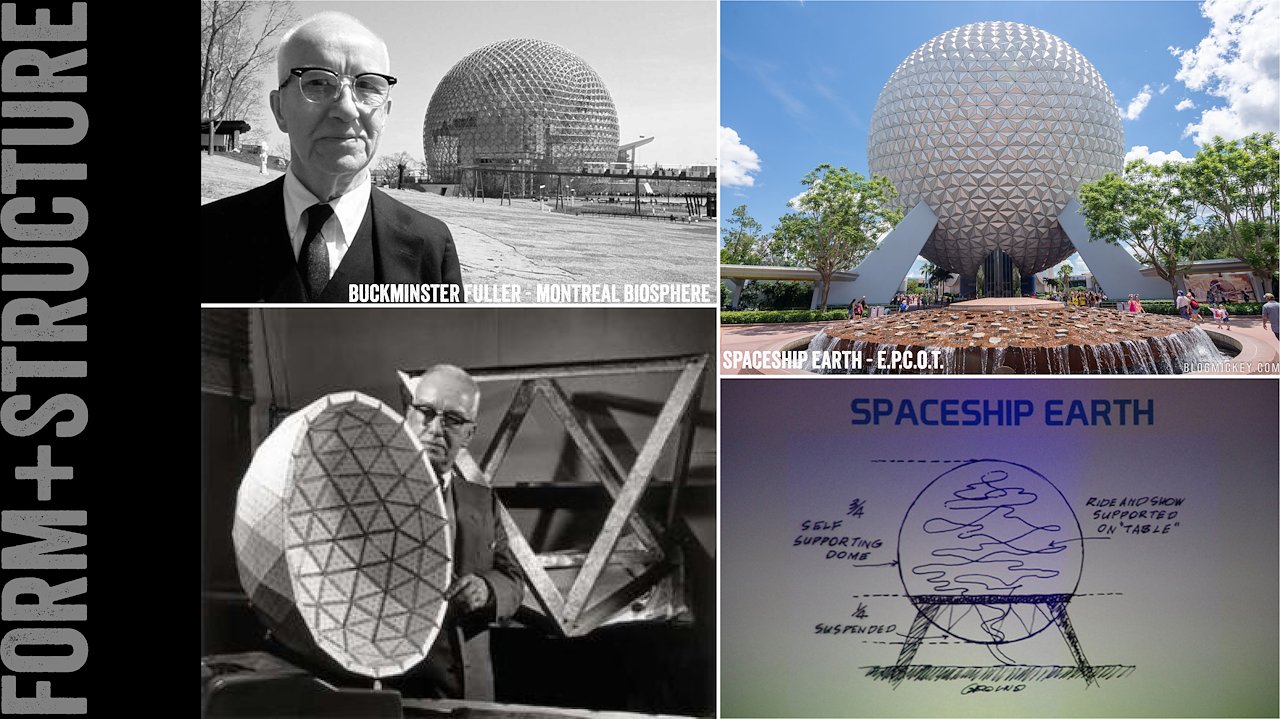

10_Form & Structure: Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic dome is a staple in every architectural history course. Although Fuller was only able to complete a 3/4 sphere at his famous expo pavilion in Montreal, Disney was able to design a structural system that allowed the dome to be lifted from the ground and suspend the last 1/4 of the dome below its main structure - thus capturing the pure spherical form Fuller was striving for.

11_Detailing: Keeping rainwater off of people, I would say, is a fairly high priority of legitimate architecture. Same goes for theme parks. The facets of the Spaceship Earth geodesic dome were designed as clever concealed rain screens, with integral drains installed around the perimeter of the dome, to pull rain water from the outside surface and send it to a predetermined location.

12_Landscape: Disney showcases an example of their immersive experiences by incorporating edible plants into all of the foliage in Tomorrowland. The story goes: in the future, space in cities will be so limited all landscape will have to serve dual purposes - such as decoration plus agriculture. Like any good design, this is not stated specifically anywhere, but the types of plants inherently provide a sense of - and reinforce - the crafted story.

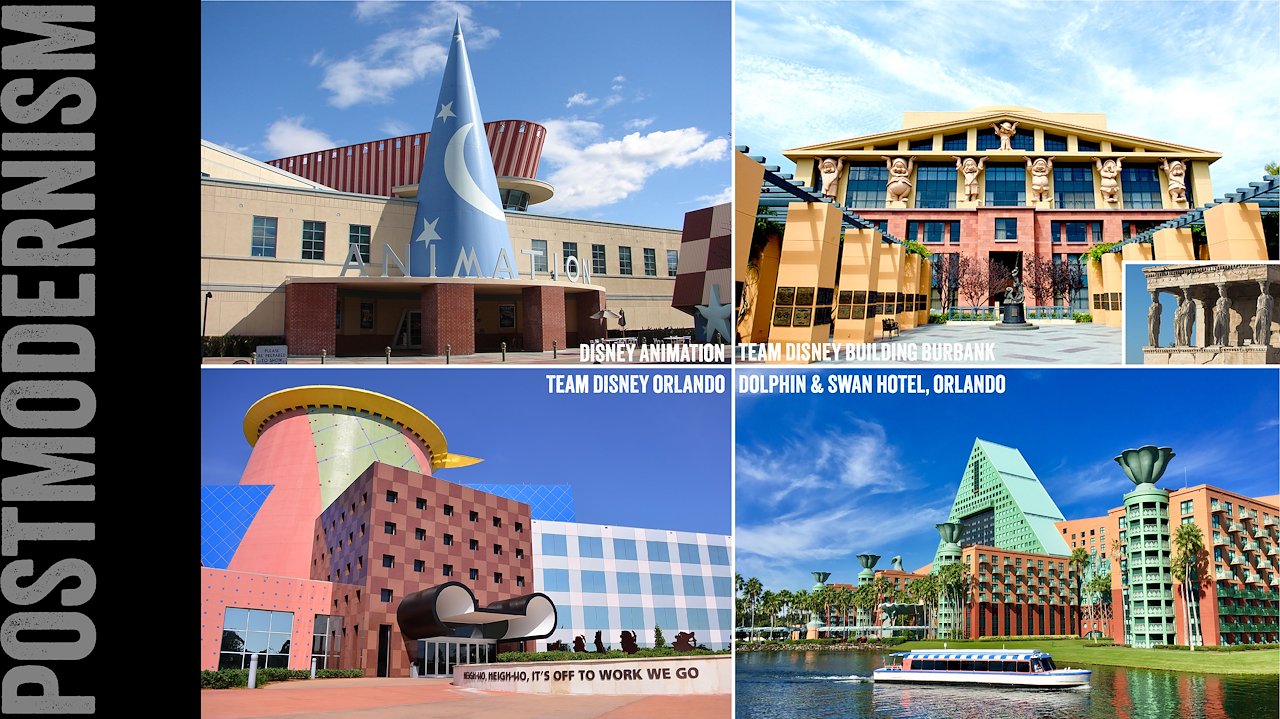

13_Context: While this may hurt my case more than it helps with some colleagues, go with me here…in what other context does PostModernism work SO well? Michael Graves’ use of pastel colors and historically inspired forms seem to finally find a place within the fictionally inspired programs of a Disney theme park or office building.

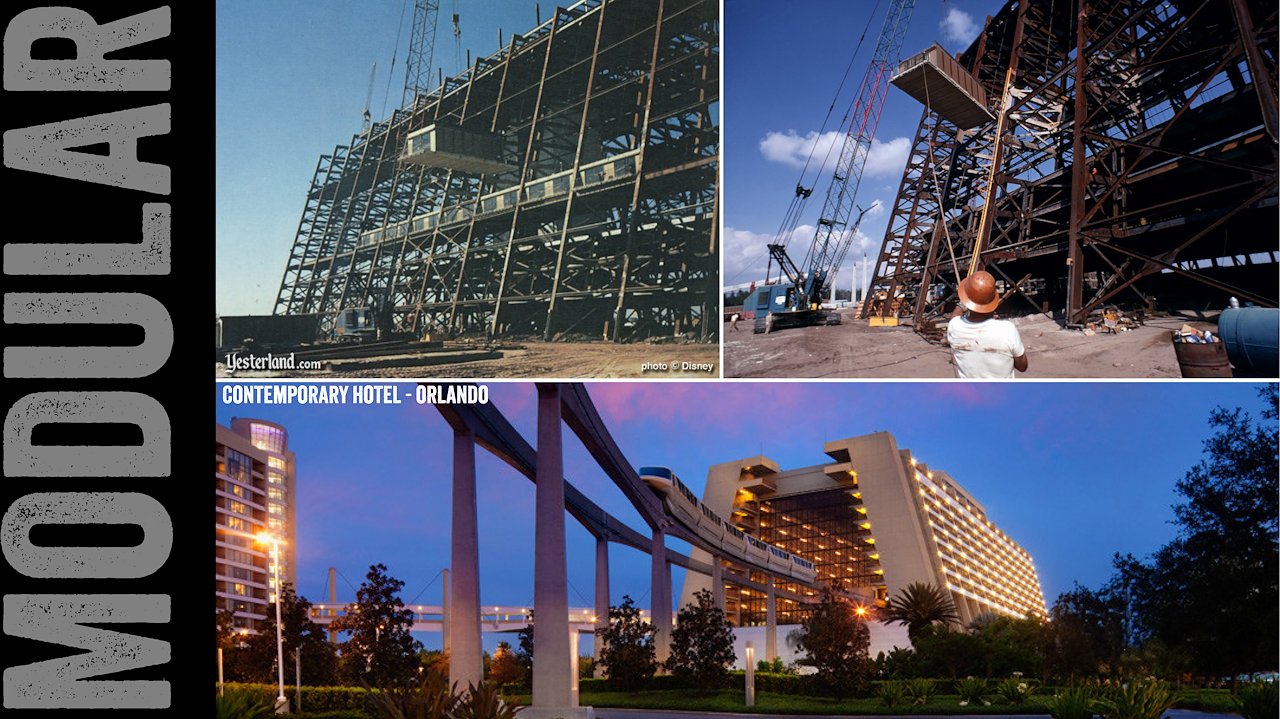

14_Modularity: What architect student did not go through school without exploring the possibilities of modular construction techniques, or even integrating public transit directly into their projects? Disney did just that in their Orlando based Contemporary Hotel. To this day I argue, the A-Frame structure and integral transit lobby highlight some of the most successful uses of such programs.

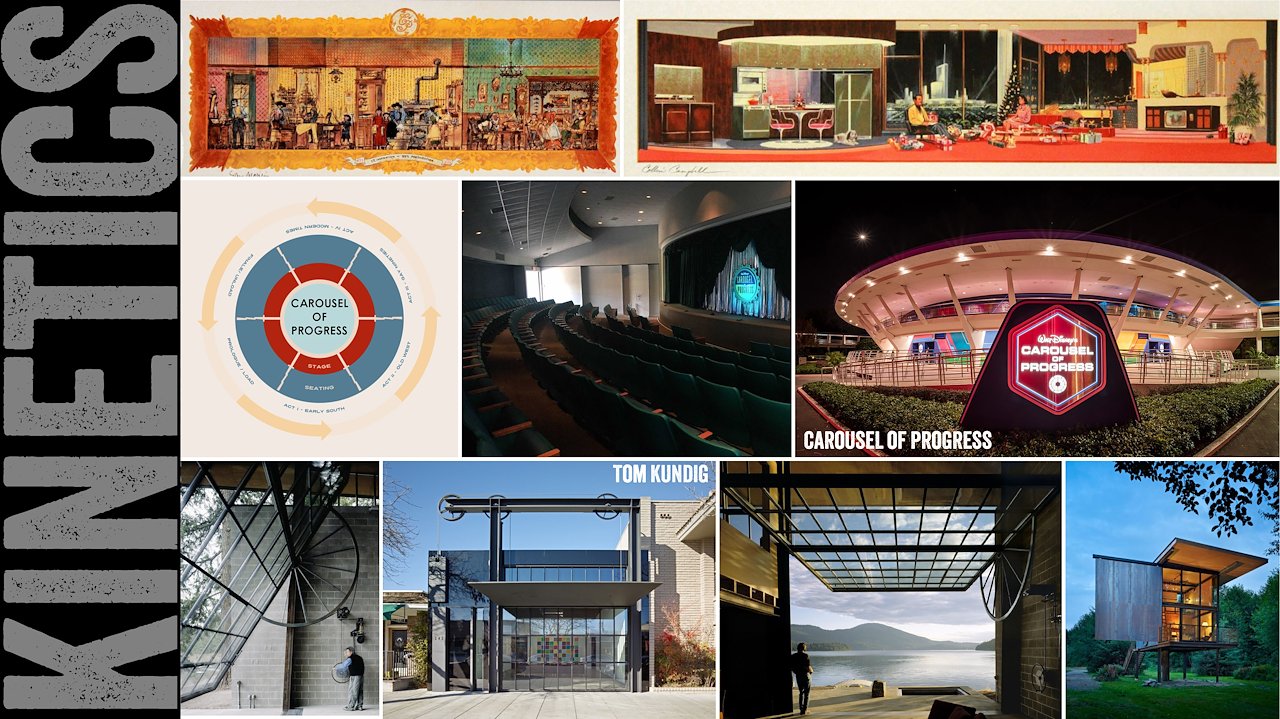

15_Kinetics: Kinetic movement are a big draw for contemporary architecture. Seattle-based Architect Tom Kundig exemplifies this with his custom apparatuses that blend the line between indoor and outdoor space. The Carousel of Progress, originally built for the 1964 World’s Fair, utilizes a fixed stage at the center of the building, in which the entire exterior perimeter – containing the seating - then rotates around, creating a dynamic effect to an otherwise static show pavilion.

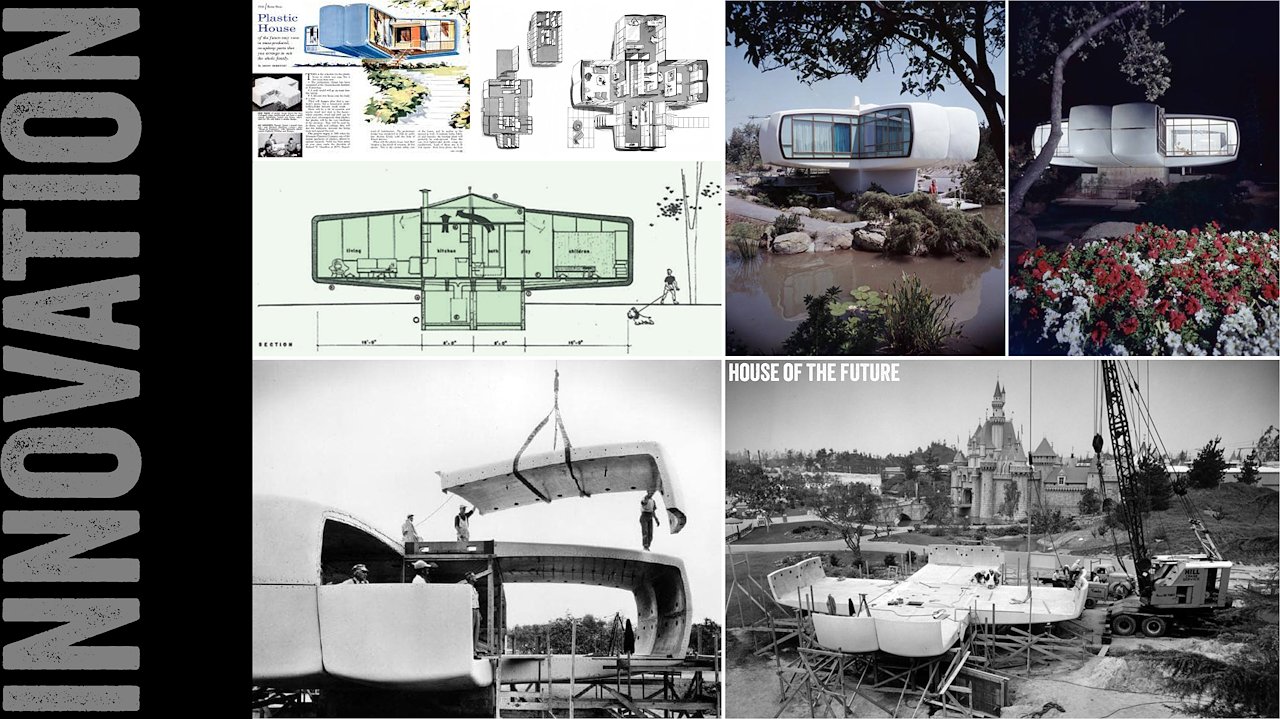

16_ Innovation: Contemporary architecture tends to push the boundaries of innovation - through materiality, form and function. All of these are evident in the House of the Future, a collaboration between MIT and Disney and displayed at Disneyland in the 1960s. From its all plastic-molded exterior panels, to its modular wings and pilotis core concept - the house provided a glimpse into a possible future of design.

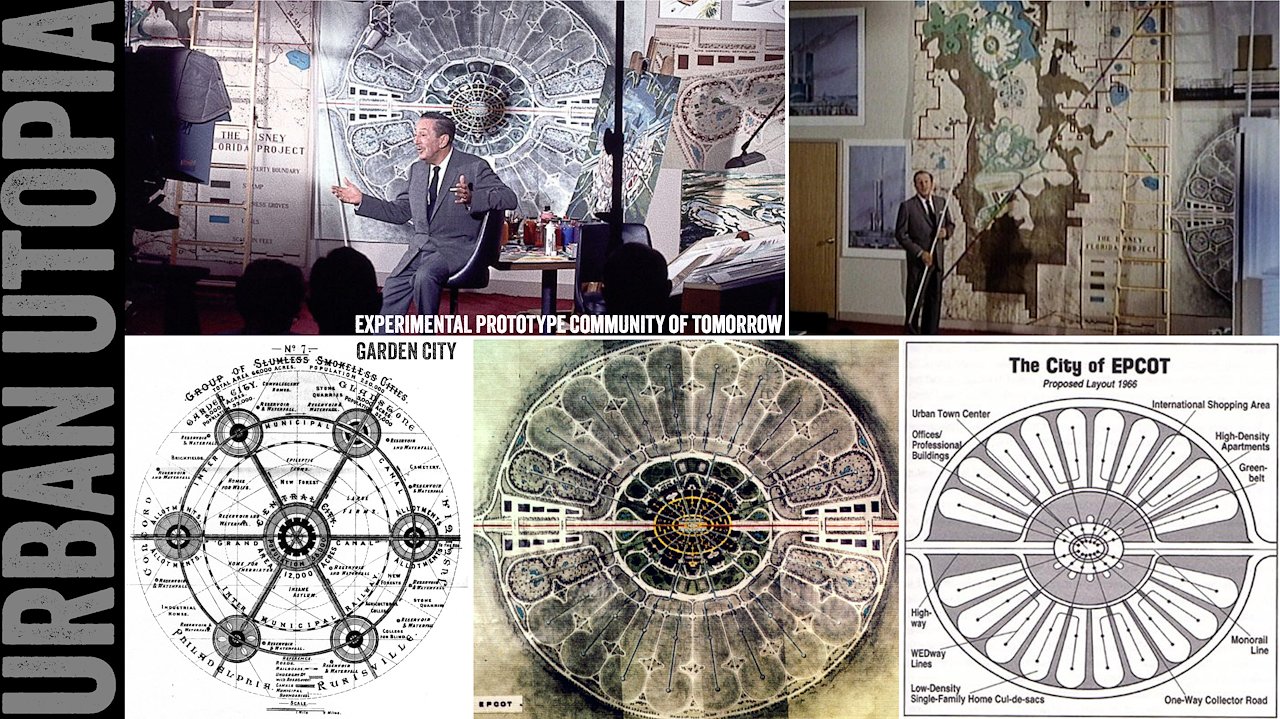

17_One of the most fascinating pieces of Walt Disney’s innovative accomplishments, was his initial designs for a utopian community known as the Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow. Using concepts from the Garden City (and the hub from Disneyland) his city concept had the potential to have done to city planning what Disneyland did to the amusement park.

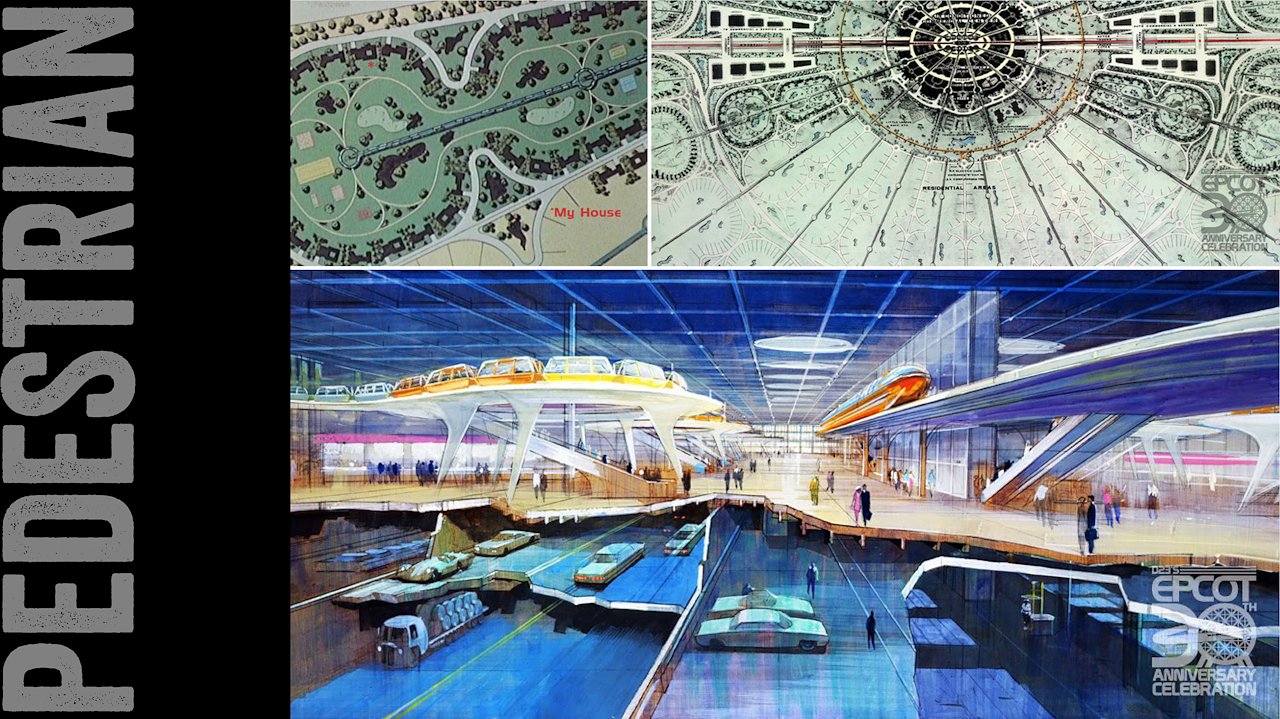

18_The design emphasized a more pedestrian centric approach, pushing cars to the perimeter of neighborhoods and utilizing People-Movers and Monorails as major pieces of public transit within the city. Unfortunately, with his death, the utopian city transformed into the theme park we have today – now known simply as EPCOT (albeit another fascinating redefinition of the theme park and one of my favorites).

19_So I put it to you - isn’t good design about the details? As Charles Eames said, “The details are not the details, they make the design.” There is a subconscious understanding that when the little details are right, we know the people behind them cared about and paid equal attention to the big picture. All of these detailed moments work together to craft a legitimate and authentic experience.

20_Whether it’s the experience of a rammed earth wall juxtaposed against tempered glass, or a broken wooden beam precariously holding up a boulder overhead in an old mining town - are we not speaking the same language? Are we not crafting authentic experiences? “God is in the details”, just as “there is no magic in magic, its all in the details.” So in that, I think there is in fact - a connection.